The inscriptions of Wadi el-Hol: The answer for historical questions

Introduction

Ever since the first material of the earliest examples of alphabetic writing was discovered by the British archaeologist Sir Flinders Petrie (1904-05), the study of origin of alphabets has become the subject of scholarly interest. From then onwards with the increase of evidences the margin of many doubtful matters in the subject has been getting narrowed. Dozens of inscriptions were discovered both from Sinai and Palestine. As such it was made possible to assert that the inventors of alphabets are Semitic people, and there exists single line of evolution for almost all alphabets of the world; indeed these assertions are just about achieving universal acceptance. Yet equally there remain unanswered historical contradictory issues. Particularly interesting the place and date of the first alphabetic writing are unresolved problems. Accordingly, the hypotheses for locating the place of invention most often have been based around the geographical locality where the oldest alphabetic inscriptions have been found. Principally these places are, the Southern Levant, Sinai and Egyptian delta (André Lemaire 2008); and the issue of dating due to imprecisions in a wider range could only be confidently claimed, i.e. somewhere within 1850-1300 B.C.

Having generally the 20th century archeological endowments played major role, in 1998 additional imperative old inscriptions were discovered by Egyptologists John Darnell and his wife Debora, on a rock face in the Wadi el-Hol (Terror Gulch), in the heart territory of Egypt. Graphically they look closer to the “Proto-Sinaitic” materials, thus there is no doubt they are Semitic alphabets. Paleographically they are more archaic than those previously discovered Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions (Hamilton 2006). I believe the inscriptions have exceptional significance in the study of origin and development of alphabets; and would answer not only the above two inquiries but several questionable scholarly issues.

The materials first and foremost provide some important evidences which can lead us to see the place for the first steps towards alphabetic system alternatively from the previous most candidate regions. In this context, the discovery of the earliest alphabetic inscriptions in non-Canaanite speaking region, and for some of the signs of the script lacking matches with the alphabets of the Proto-Canaanite or Proto-Sinaitic, which altogether could weigh against the most favored view which regards the Northwest Semitic-speaking people as inventors. And at this level I argue that it is premature conclusion that to assume the script found in Wadi el-Hol are in West Semitic languages or in category of the North Semitic alphabets. Therefore the reconstitution of the family tree for Semitic alphabets has to largely lie on complete data collections from all-round areas related, directly or indirectly, with Semitic people. Here it must not be forgotten, good linguistic approach for analysis has to be thought as indispensable prerequisite. As long as the issue of inventors is concerned, the language which the scripts represent is more important than the place where they were discovered.

Secondly, taking the contents and the models from which some signs developed as reference points, it might be made possible to set the date of the early Semitic alphabetic writings more precisely with the help of these inscriptions than any else. While the research paper puts the interpretation of the inscriptions of Wadi el-Hol in its central intention; it is noteworthy to make clear that the paper covers very wide important issues, in actual fact it can be thought as a critical review on the general scholarly subject “origin of Semitic alphabets”.

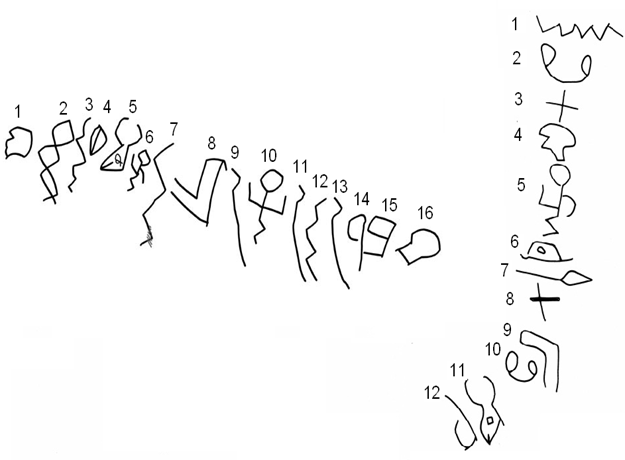

Fig. 1 The two inscriptions of Wadi el-Hol; as shown the two texts written in vertical and horizontal directions, containing 12 and 16 individual signs respectively. They are found on the same rock spur, only a separation of few feet in between them (Colless, 2014); and both of which are on a vertical cliff face, roughly 4 1/2 feet off the ground (Co-authored with: Leta Hunt, Marilyn Lundberg & Bruce Zuckerman, 2001).

Technique of Interpretation

It is undeniable fact that the two Wadi el-Hol inscriptions in many ways could be the most challenging to decipher, accordingly require a task of thoughtful handling. As such many techniques were used for rationale analysis in order to come to precise reading of the individual signs, and the texts. Of which the attempt of comparison with the signs of South Arabian (or the most alike “old Geez”) particularly have played fundamental role in this analysis, and appeared substantially to demystify the mysterious inscriptions. Since the signs appeared to have a close connection with those alphabetic systems, they have been broadly analyzed in this paper. On the course, some set of rules of derivation for some letters of these alphabetic sets was discovered. Ten of the South Arabian alphabets, nine of them have counterparts in Old Geez, seem to have been developed from the Ten Words of Mosaic, as they appear to symbolically reflecting the ideas portrayed by the Ten Words. Clearly, their original purpose was not to serve as alphabets of these systems.

In this interpretational process the synonymous Proto-Sinaitic material simplifying the total puzzle almost by half percent. From this vantage of analogy between these sets of alphabets, the following characters have straightforwardly deciphered; depending on the Albright’s chart: V1, H3, H7, H12 = ‘M’; H9, H11, H13 = ‘N’; V3, V8 = ‘T’; V11, H5 = ‘A’; V12, H14 = ‘L’; V6 = ‘‘A’; H15 = ‘B’; and H10 = ‘H’. Most of the time all these Proto-Sinaitic counterparts are undisputable in the account of scholars, and among them who have perfectly agreed is Darnell.

On the other hand, the challenging parts in working on decipherment of these inscriptions: firstly the direction of writing is not easily identified, and secondly the words are indistinguishable as there is no separator that serves for portioning the sequence into separate words. Therefore as basic and strategic as it is, identification of the right direction of the writing should be a preceding step. The basic misleading in the previous interpretations was in this matter; a perpetuating of wrong direction of reading for the horizontal case, considers right to left. Generally, it is disastrous to depart deciphering from unsure direction of writing which its consequence affects everything. Thus, it is much better to treat the vertical inscription first, its direction of reading is plausibly deterministic, as it is too natural to move from top to the bottom particularly for lengthy sequence. If we are successfully reading correctly for the signs (and importantly also the words) of this inscription, it will be only a work of deciphering two signs (H2 & H4) for the horizontal (the rest are automatically transcribed in reference to the Proto-Sinaitic signs). Then its direction can be identified from the recognized orthographies which are already composed from the deciphered letters.

The ten Mosaic signs: “written in fingers of God”

The South Arabian alphabets (or Old Geez) might be thought as the most conservative of ancient characteristics. Appeared to preserve complete set of consonantal letterforms, in which its total number of letters fitting the Proto-Sinaitic letters. And it would serve as intermediary tool which help to connect us to an earlier account of symbolic significances. Their predominant feature is recognized by smoothed form of letters, which are quite linear, upright, and apparently regular subgroup patterns. Despite the high degree of the letter shapes’ smoothness, they remain as fully informative. Their original pictographic nature which identifying the meaning of the object still remnant there, at careful examination they are reconstructible. The letters in this alphabetic system were developed from different category of objects. And some group of the letters identified to have been extracted from hand, palm and finger shapes.

The practice of finger or hand gestures have been the culture of many people beginning from antiques, and their significance can be traced in different symbolisms: in Egyptian the finger used as symbol for 10,000 in numeric system; in Near Eastern measurements we find the palm “Tefah” an equivalent of fingerbreadths “Etzba’ot”; and in the alphabets of North Semitic the letter “Kaph” palm. Such adoption is largely attested in the South Arabian alphabetic system, surprisingly we find ten of the 29 letters traced their graphic forms in finger, restructured fingers, and with few involve the gesture of hands. The tradition is shown partly in varieties of letters of other alphabetic systems, quite essentially is the script of Wadi el-Hol. This point is not only useful for the thought of common ancestral for alphabets, but also the misrepresentation of complete set of symbols in the other alphabets can be used as a tool for study of paleography. And the central place behind the derivation of this set is, as I have already mentioned earlier, visibly the ideas in the Ten of Mosaic Law. The ultimate purpose of reestablishing the frame of origin for these ten alphabets is to decipher these inscriptions of Wadi el-Hol, in which five signs of these ten are found in these inscriptions; the rest five also believed included in the complete set of this ancestor script.

1. The gesture of worshiping

There are certain reasons to take the figure as the modified version of the Wadi el-Hol sign H10, which is a figure of a person raised his hands; it is often interpreted as dancing in celebration (Gardiner A28). In almost same outlook I see it as a worshipping person. It is thought that the symbol was used to write Semitic Halleluyah (the sound H). Again the parallelism in phonetic value besides the graphical appearance may lead one to consider confidently that the sign H10 as a proto-type of the first South Arabian letter (![]() ).

).

Thus the Mosaic commandment that corresponds to this figure of worshiping is the first commandment “thou shalt worship no other god”. Indirectly denoting “you shall worship only Yahweh”.

Fig. 2 The hieroglyphic of A28

2. The gesture of grasped pair hands ![]()

As it is shown in Fig. 3, an Eritrean rock painting depicts a figure of two men with both holding hands; they look in the usual display style to the couples of Gemini in the Arab Zodiac. The shape of their figure is comparable with the South Arabian ‘d’. Gemini in Arab’s zodiac is called “tawman” which is close to Heb. tumnha, meaning likeness image. In the Biblical point of view the instruction “love your neighbor as yourself” found to work as substitute for the prohibition of 2nd commandment, (Ex 20:4-6) “You shall not make for yourself a graven image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth” . . . and showing mercy to thousands of those that love Me and keep My commandments. The substantial object of God’s representative is Love, meaning when some loves his neighbor he holds the express image of His essence of the unseen God in his thoughts, the idea is understood from (1st John 4:20), “… for if he does not love his brother whom he has seen, how can he love God whom he has not seen?”.

Fig. 3 Hand to hand figure of two men from Eritrean rock

3. The gesture of fighting  Or

Or

This Wadi el-Hol sign (V5) depicts the figure of a person holding a stick or club. The sign of club holder in South Arabian or Old Geez alphabets case, according to this discussion, is identified with character A (see Fig. 10 and its descriptions there). However the Phoenician Yod is doubtlessly an exact version of V5; another in similar form is shown in Fig.4, which is a frequent symbol in Eritrean rock art. These forms are not reduced of V5 as they seem, rather oddly they are the original ones. The reason why these figures possess a theme of fighting man stylized in this specific shape is presumably due to the celestial Archer, however such shape is discovered in the star pattern of modern Scorpio (Fig.5), since originally the shape belongs to Archer; either because the two were merged to common figure (Paul Carus in his Zodiac of all nations, p.p 467) or the star pattern explicitly belonged to Archer but later shifted to configure Scorpio for unknown reason. Ultimately, we understand that the symbol has something to do with an expression of fighting, thus it stands for the 6th comm. “Thou shalt not kill”.

Fig. 4 The Kortamit Stylistic Archer (from P. Cervicek, 1976)

Fig. 5 The star pattern of modern Scorpio

Note: The following seven letters unlike the above three hand gestures are derived from finger gesture.

4. The stylistic finger

This sign signifies a stylistic finger in which the circle at the top implies the nail, and its lower part of the finger simplified to a single line. Intrinsically this stylized detached finger may not have any value, but its deliberate meaning have to be seen in conjunction with the four fingered Proto-Sinaitic kaph. It seems that as distinctive symbols they begin to be used only afterwards in the alphabetic stage of writing. They seem to suggest that the act of punishment to the person who robbed by cutting off his finger. Though no such punishment is attested in Mosaic Law, it was common in primitive cultures. The sign crossed by horizontal line (![]() ) can be taken as ideogrammatic variant, despite they represent for distinct sounds, in which the crossing may denote canceling or omission. Ultimately, the ideograms would be compared to the 8th comm. “Thou shalt not steal”.

) can be taken as ideogrammatic variant, despite they represent for distinct sounds, in which the crossing may denote canceling or omission. Ultimately, the ideograms would be compared to the 8th comm. “Thou shalt not steal”.

5. The gesture of pointing

We observe the same stylistic finger placed at the edge of an arch. It denotes a closed fist having only the pointing finger extended upwards. It may also indicate for the little finger, but my opinion simply rest to the pointing gesture. Because the gesture of pointing-finger is generally considered as the indication of pointing to somebody (or something) which is in view or for an object in presence. The notion that reminds to the expression of name of God “I am that I am” in Biblical context (Ex3:14). The Hebrew renders the term I am as “Hayah”, it merely mean “to exist”. It may be compared to the Amharic term “Yihe” or “Ya”, meaning this or that resp. In Tigrigna “Ya” is found as an interrogative word used when someone needs confirmation “is it or is that?”. Probably these varieties are the only relics in Semitic dialects as they match to the name of the Israelite God Yah (a contraction of Hayah). By the same context, El, Eloah, ‘elah, the appellation refers to God/god, all these kindred words etymologically might come from “Alo”, in Tigrigna “present”; we might also trace it in the Hebrew ‘el “these or those”.

The Tigrignian grammatical word “Zi” (“Za” for feminine), meaning this, can be creditable enough to explain the acrophone Zah ( ). Moreover, it is not difficult to trace Etzba (finger) in the Hebrew term Ytzba “present”. This suggestion importantly affirms the relation between the above notion “existing or present” and the gestural communication. From same perspective, we can construe the letter name made by the above symbol (

). Moreover, it is not difficult to trace Etzba (finger) in the Hebrew term Ytzba “present”. This suggestion importantly affirms the relation between the above notion “existing or present” and the gestural communication. From same perspective, we can construe the letter name made by the above symbol (![]() ), in the South Semitic context, as Tig. “Yelen” or Amh. “Yelem” (equivalents of Heb. ’Owlam), which can be worthy of explaining the acrophonic requirement. All these words rendered as “absent” or “conceal”; the Hebrew word has additionally translated as “eternity” or “long time”. The basis for this pun would be the Egyptian finger, the symbol that stands the numeric ten thousand; it turns out to explain long length of time and the detached finger at once. It is important to remember that here it is employed the finger (the symbol of 10.000) for infinity, unlike the Egyptians system that they use the seating god (the symbol of 1.000.000).

), in the South Semitic context, as Tig. “Yelen” or Amh. “Yelem” (equivalents of Heb. ’Owlam), which can be worthy of explaining the acrophonic requirement. All these words rendered as “absent” or “conceal”; the Hebrew word has additionally translated as “eternity” or “long time”. The basis for this pun would be the Egyptian finger, the symbol that stands the numeric ten thousand; it turns out to explain long length of time and the detached finger at once. It is important to remember that here it is employed the finger (the symbol of 10.000) for infinity, unlike the Egyptians system that they use the seating god (the symbol of 1.000.000).

The 3rd comm. speaks in relation to the name of God “Thou shalt not take the name of the LORD thy God in vain”.

6. The gesture of denial covetousness

This is the second sign in the Wadi el-Hol vertical text; the symbol was made from the stretched thumb and little-finger, keeping the rest fingers contracted. The slight difference of the size of the circles cannot be taken as mere accident, because the portrayal with this sort appeared in both cases (V2 & V10), and can finely signify the considerable distinction between the fingers.

No exactly such letterform in South Arabian alphabets is identified. However, the character ‘R’ ( ) might be attributed as a modified version of this proto-type; the difference is simply the South Arabian (old Geez) alphabet is smoothed one, i.e. the two circles at the tips are missed. Possibly the reason for the omission of the circles would be to avoid confusion with letter ‘M’ (

) might be attributed as a modified version of this proto-type; the difference is simply the South Arabian (old Geez) alphabet is smoothed one, i.e. the two circles at the tips are missed. Possibly the reason for the omission of the circles would be to avoid confusion with letter ‘M’ ( ), Since the letter ‘m’ apparently at its latter stage resembles to this Wadi el-Hol sign, i.e. the curved side of the letter gets collapsed, modified from

), Since the letter ‘m’ apparently at its latter stage resembles to this Wadi el-Hol sign, i.e. the curved side of the letter gets collapsed, modified from  to

to  .

.

The distancing of the fingers might symbolize the idea that not to have any tendency of covetousness on others’ possessions. The last comm. says “Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s house, thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s wife, nor his manservant, nor his maidservant, nor his ox, nor his ass, nor any thing that is thy neighbor’s”.

7. The gesture of honoring parents

The shape indicates the gesture of two adjacently joined pointing fingers of the left and right hands. The nails and the lower finger parts are represented by common circle and line. It is clear that the wider in size from the letter Zah (![]() ) shows the outcome of two hands unlike to that formed from single hand. The significance of the sign is certainly noticed in association to the 5th comm. of Mosaic Law, the coupling can mark the comprising of father and mother, that says “Honour thy father and thy mother”.

) shows the outcome of two hands unlike to that formed from single hand. The significance of the sign is certainly noticed in association to the 5th comm. of Mosaic Law, the coupling can mark the comprising of father and mother, that says “Honour thy father and thy mother”.

8. The gesture of denial of adultery

Following same artistic standard, the gesture seems to involve perpendicularly adjoining of two fingers. The connected nails of the fingers are represented by a common single circle, but the palm and the other three fingers in this case are totally avoided just for desired simplified representation. The Proto-Sinaitic equivalent depicts two connected circles, and seems to imply the exclusive joining of the nails. Naturally two fingers can be perpendicularly connected only in the gesture that involves the thumb with any other finger, and in gestural tradition most often we find it coupled with the pointing finger, and displaying variety of meanings depending on the type of region. Despite the various interpretations, bearing the Mosaic 7th law in mind “Thou shalt not commit adultery”, in which the loop formed from joining of the thumb and the pointing finger may indicate the covenant ring (or union), and the three fingers may connect to the involvement of third party in the union of two partners, in oppose to the right marriage covenant made by only two opposite sex; showing simply a situation of adultery. Probably the gesture will have opposite signification, i.e. as denial adultery, when the hand is waved, since such gesture in some tradition is used for warning. The interesting thing here is the capability of the letter name as “Qelebiet”, meaning “ring” or “Qolephe”, meaning “to bind” in Tigrigna, the basis for the acrophone Q. The assumption still in line with the letter name Qoph of Hebrew, proposing the name may relate to the Hebrew root “Qavah” translated as “to bind together”.

9. The gesture of cessation from labor  Or

Or

The sign V4 (and the other two examples, H1 & H16) has been widely thought as the character of ‘R’, due to similarity with the Proto-Sinaitic sign for ‘R’ resh, the direct pictograph of human head. Clearly, this assumption lacks critical thoughts for it was only made from rough approximation to the shape of head. A simple explanation can be offered for devaluing the assumption is: if the sign stands for head, why the facial parts were missed in contrary to V6 (the eye glyph) & V11 (the bull’s head) which are presented with detailed features. Again if the latter versions of Proto-Sinaitic R include detailed face structures (such as eye, nose and other minor marks) then this question must be asked: how can this Wadi el-Hol alphabet which is supposed to be the earlier version (or contemporary) be relatively a simplified one? As everyone expects paleographically simplification and smoothing of the letter shapes is most often a later stage of development.

Like the above symbols it was supposedly derived after shape of palm and finger, and signifying simply a clenched hand where all the fingers are closed. The ultimate signification of this gesture might be cessation from labor, i.e. the “shabath” Jewish 7th day, which is literally translated as “to cease”, which says “…the seventh day is the sabbath of the LORD thy God: in it thou shalt not do any work…”.

Following same procedure of style which is applied in the previous alphabets of South Semitic (like for example ![]() ,

, ![]() ), we will obtain an arch shaped if all the fingers are contracted. Such desired letter (

), we will obtain an arch shaped if all the fingers are contracted. Such desired letter ( ![]() ) is shown among the Thamudic alphabets, used to represent the sound S which is a closer phoneme to the supposed acrophone Š. It must be noted that it is difficult to compare to the arch shaped South Arabian letter ‘B’ (

) is shown among the Thamudic alphabets, used to represent the sound S which is a closer phoneme to the supposed acrophone Š. It must be noted that it is difficult to compare to the arch shaped South Arabian letter ‘B’ (![]() ), rather I trace this character to the figure of bull’s horn which is attested in similar form in the astronomical paintings found at the site Danga, Eritrea (Storia de Ethiopia, p.145 n. 159), standing for Taurus. The South Arabian character ‘B’ is simply the result of inversion, the possible root of acrophone would be “Bie‘ray”, bull in Tigrigna. In South Arabian (or old Geez) the character S is the possible sign styled after the clenched-hand gesture, where the mark above the arch would be added to be distinguished from the letter ‘B’. Hence we can convincingly predict the value of the sign among the sibilants S or Š.

), rather I trace this character to the figure of bull’s horn which is attested in similar form in the astronomical paintings found at the site Danga, Eritrea (Storia de Ethiopia, p.145 n. 159), standing for Taurus. The South Arabian character ‘B’ is simply the result of inversion, the possible root of acrophone would be “Bie‘ray”, bull in Tigrigna. In South Arabian (or old Geez) the character S is the possible sign styled after the clenched-hand gesture, where the mark above the arch would be added to be distinguished from the letter ‘B’. Hence we can convincingly predict the value of the sign among the sibilants S or Š.

10. The gesture of keep unspeaking

Here the gesture includes additional body part (the mouth), and required to convey for an extensive meaning. The sign depicts a finger laid on a mouth. This gesture universally used to signify “shutting the mouth” or “to keep unspeaking”, translated in Semitics as “tim”, seems to be the source for its sound value Th (t). The assumption still works with the common mouth used to write the Phoenician or linear Ugaritic Pe (>); its combined effect with the stylistic finger seems to yield the South Semitic ( ), the character Th (t), which also agrees in phoneme (see for this South Semitic sign (

), the character Th (t), which also agrees in phoneme (see for this South Semitic sign ( ) in the A.G Lundin’s chart, Ugaritic writing and the origin of the Semitic consonantal alphabet: Aula Orientalis 5(1987b), p.p 95).

) in the A.G Lundin’s chart, Ugaritic writing and the origin of the Semitic consonantal alphabet: Aula Orientalis 5(1987b), p.p 95).

The gesture of shutting the mouth can be compared with 9th comm. “Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor”.

Comments are currently closed.