The inscriptions of Wadi el-Hol: The answer for historical questions

The attestation of the Mosaic Commandments

The attestation of the Mosaic Commandments

with the gestural symbols

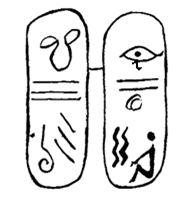

A. The Timna inscription: The direct association of the gestural symbols to the Ten commandments of Mosaic might be evidently confirmed by the discovery of Timna inscription (Fig. 6), which principally attests an ideogrammatic type for the writing system of the original Ten Commandments in particular, and would answer the speculative issue “the type of writing system of the Pentateuch” in general. The inscriptions are inscribed in cartouche-like oval rings (see Fig. 6). Interestingly they have an interconnecting line between the two ovals; definitely an indication of the written material as two paged like the Tablets of Moses. The opinion that the ovals as an attempt to design tablets is also supported by Wimmer and Colless.

Fig. 6 Timna rock inscription

Coming to their details, in the left oval: on the top we encounter with sign which may well be related to our 6th gesture (V2 or V10 in Wadi el-Hol inscriptions). The sign was further stylized here becoming a modified form, for this we can’t find it in its exact original form. In this portray it was designed to look the human eyes along with nose. Below it there are three strokes. Next to them we find the alphabet lamied like sign having its lower part more curled, and importantly a dot beside it. On its right side, there are three other obliquely paralleled strokes.

In the right oval: on the top, a sign depicts an eye glyph. Taking into account the small marks as part of the eye; despite to the contrary Wimmer’s suggestion which he ignores the marks, considers them as not coherent and unintentional marks, I want to relate it specifically with the udjat-eye (the eye of Horus, D10). Beneath the eye glyph there are two horizontal strokes, and next to them a circle made by depression. In the lower part of this oval, we observe double wavy lines and the seated person placed side by side.

Interpretation: I should note that I quoted many verses from the Bible especially from the book of Proverbs. Especially in Proverbs and Song of Solomon there are so many parallelisms with other sources which are outside the Hebrew literature. However, because of deepness nature of the materials it makes difficulty to understand and it will be too hard to reconstruct parallelisms.

Owing to the paired Mosaic like tablet and the gesture of denial covetousness, the material tend to suggest that dealing particularly to the 10th comm. The inscriptions in the tablets appeared to display antithetical parallelism: a literary style which consists of two contrast ideas, one idea is the opposite of the other idea. Such tradition is very common in wisdom literature like book of Proverbs (e.g. Pro14:16 “A wise man fears, and departs from evil: but the fool rages, and is confident”). The eye is common in both the ovals, since the act of covetousness or not to covet is expressed in terms of sight. But they differ in that there is a singled eye in the right oval while two eyes for the other. Their significance is also contrary, the idea in the left oval has good implications. The rationale behind for stylizing of the “gesture not to covet” (![]() ) differently is for this reason, i.e. additionally to portray the eye or the idea “sight”, and needed to convey the urge “that one not to fall his eye evilly on other possessions” which is a central theme in the commandment. Regarding the equivalence to the sign (V2), both Wimmer and Colless again agree but with different symbolic implication. In contrary, the udjat-eye (in the right oval) may mark the evil act “covetousness”. Without any doubt the selection of this particular symbolism is purposeful, for the god Horus to the Israelite is rather abomination.

) differently is for this reason, i.e. additionally to portray the eye or the idea “sight”, and needed to convey the urge “that one not to fall his eye evilly on other possessions” which is a central theme in the commandment. Regarding the equivalence to the sign (V2), both Wimmer and Colless again agree but with different symbolic implication. In contrary, the udjat-eye (in the right oval) may mark the evil act “covetousness”. Without any doubt the selection of this particular symbolism is purposeful, for the god Horus to the Israelite is rather abomination.

Let’s come back to the left oval; the horizontal three stokes, being supposed as rods, would symbolize law which has three levels. The picture below them depicts man’s face, where the curled lamied stands for his nose and the dot for his eye. The three oblique strokes I proposed as thrown arrows, the way they obliquely inclined is just for this reason. Being these arrows in front of his eyes would mark that the temptations of evil are under control of him. Quite parallel with what we read in Pr 22:3 “A prudent man foresees the evil, and hides himself”. It can also be compared to the idea in Pro20:8 “A king that sits in the throne of judgment scatters away all evil with his eyes”).

In contrast, the right oval marks the consequence of trespassing the law. On treating together the double wavy line with the seated person: the seated person can be seen as a person (conventionally a woman) who takes off her close and becoming ready for washing her body in the river. And the combined evil eye (udjat-eye) and the naked woman would signify that the idea to look a woman with lust. For this oval there is a circular depression which takes the place of the third arrow. This may imply a pit and also a pierce in body because of an arrow. The similitude figures, the arrow and the pit, tell us if one gives his back to the law, definitely he is in charge of the piercing arrow and ultimately will fall to the pit or hell. Hence in any case if the horizontal ones replaced by their corresponding circular depressions, the expression does mean a situation of trespass.

A person before comes to an action of, particularly unintentional adultery, coveting with eyes and chatting with adulterous issues which are usually the steering environments for action adultery. These three things might determine as to whether the constituents consist of, three exclusive strokes (as attested in the left oval) or a combination of them (as in the right oval); or possibly different combinations from these though they are unattested yet (e.g. three pits or two pits & one stroke).

For more elucidation let’s see what the book of Proverbs suggests; the pit is attested in three different occasions of description of adultery in this Book.

Pr 22:14 “The mouth of strange women is a deep pit: he that is abhorred of the LORD shall fall therein”

Pr 5:5 “Her feet go down to death; her steps take hold on hell”

Pr 23:27 “For a whore is a deep ditch; and a strange woman is a narrow pit”

The first verse is quite clear, denotes chatting with adulterous issues. In the second verse, to follow every of her steps it merely means to fall your eyes upon her, that shows covetousness. The personification of her with pit in the third reflects that anyone who commits adultery with her falls directly to the pit. The first two verses illustrate the ways to the idea in third verse, an action commission.

Now let’s back to the right oval; since it consists of a single pit and two strokes, it indicates violation of one of the three levels of the law. According to the explanation offered the violation is in covetousness.

I don’t think the story written in the Bible (1 Sam20:20-22) is a mere coincidence. We read Jonathan and David used a secret signal. Jonathan is to shoot three arrows; if the arrows fall before the young man, it means things will be alright. But if they fall behind him it means the opposite. The story we read in these passages entirely associated in reference of the ideas in these ovals. The ideogram with this particular symbolism must have a widespread recognition in those times. Jumping to verse 30, we simple get “Then Saul’s anger was kindled against Jonathan, and he said unto him, Thou son of the perverse rebellious woman, do not I know that thou hast chosen the son of Jesse to thine own confusion, and unto the confusion of thy mother’s nakedness?” Regarding the absence of David in the king’s table Saul claimed that it would be due to uncleanness (1 Sam20:26). This uncleanness in Saul’s thought of suspect could directly relate to a heart of covetous desire towards his wife; thus that is what he meant by to the shame of mother’s nakedness. Clearly such transgression derives great anger which deserves a rush punishment without any arraignment. Solomon in Pro27:4 states that the greatest anger is the anger provoked because of envy. Saul was probably hypocrite in this matter, his sudden throw of the arrow toward David or Jonathan just to convince that on the basis of fair condemnation.

B. The Gezer sherd inscription: Interpreters quite often see this inscription like the Timna inscription as an alphabetic text, since all the signs are found in the Semitic alphabetic sets. However there is still a possibility for the inscribed Gezer potsherd to be an ideogram writing, where the kaph & waw jointly indicate the 8th commandment itself, and the square simply signifies the tablet (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7 The Gezer sherd inscription

The adoption of Mosaic gestures in the

titles of Semitic numerals

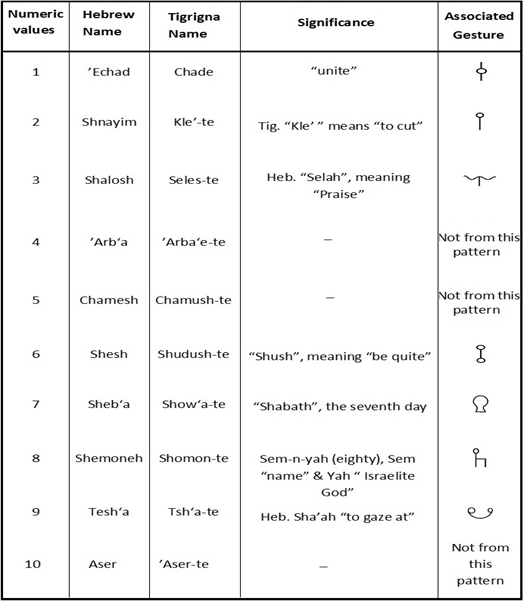

The Semitic names for seven of the first ten cardinal numbers appeared to have their origin from this set of gestures. In this part of discussion the etymological process for these names in comparison with two Semitic languages, Tigrigna and Hebrew, was established. It must be noted that I treated the Tigrignian words exclusive of the prefix “te” which is found in pattern in all except for the first case (Chade). It is only a modifying element, probably it was added for the sake of femininity or plurality. This particular discussion can be taken as further verification for the significance of the gestural symbols from different angle.

• The word for numeric one in all cases is pronounced almost similarly, ’Echad, Chade, the base word for these varieties might be translated originally as “unite”. Thus the symbol for the gesture which made from the adjoining of two fingers (![]() ) would be supposed for the derivation of the word.

) would be supposed for the derivation of the word.

• There is a major difference for the name of the second cardinal between the Tigrigna and Hebrew. The title used in Tigrigna is “kl’e-te” unlike Shnayim of the most West and East Semitics. The base word “Kle’ ” would be rendered “to cut or to remove”. Not only comparably it gives excellent sense with the sign (![]() ) but also might seem to have come artificially from the initials of the well-known Biblical phrase “Ki Le ’Olam Chesdo”, in Hebrew mean “for his mercy endures forever”. In this way it is possible that one to construct a connection with our hypothesis ’Olam, which we have earlier attributed for the name of the letter. Further from this thinking it might be noted that it appeared to be the basis for the Tigrignian phrase “Qel ’alem”. It is usually used in the instance, when one is asked to help his self if he refused while he wanted, such pretense is called in Tigrigna “Qel ’alem”. The term originally might have applied to vow, to mean not to do something despite of the forceful request; i.e. let my finger be cut if I do that.

) but also might seem to have come artificially from the initials of the well-known Biblical phrase “Ki Le ’Olam Chesdo”, in Hebrew mean “for his mercy endures forever”. In this way it is possible that one to construct a connection with our hypothesis ’Olam, which we have earlier attributed for the name of the letter. Further from this thinking it might be noted that it appeared to be the basis for the Tigrignian phrase “Qel ’alem”. It is usually used in the instance, when one is asked to help his self if he refused while he wanted, such pretense is called in Tigrigna “Qel ’alem”. The term originally might have applied to vow, to mean not to do something despite of the forceful request; i.e. let my finger be cut if I do that.

• The name for numeric three is Shalosh in Heb. and Seles-te in Tigrigna. I suppose it would be traced from the well known Heb. “Selah”, provided that the ‘sh or S’ is assumed as merged externally. The significance of the word according BDB is “Praise”, from breaking the word into S & lah. It is fairly common practice in many cults that at daily basis worshiping or ritual activities are performed three times. Such tradition is historical that goes back to the remote antiquities. This could be the basis how it was come from Selah. I just introduce a new pattern of worshiping symbol (![]() ) which would explain the theme better than the first South Arabian letter or Halleluyah Sign (A28); the especial symbol is attested in one site of Eritrea, Adi Qunsa (Vincenzo Franchini, 1964). Four series of this symbol found to be carved on rock surface in that site; where one is slight different from the others. Taking into account the significance of the more stretched hands of A28 (or the first South Arabian letter), the slightly lowered hands may signify a silent type of worshipping unlike that accompanied by dancing or shout singing. The logic behind this assumption is the literal meaning of “Selah”, which is also translated as silent in Tigrigna or in Hebrew. I would like also to note that the breast like Proto-Sinaitic character ‘S’ seems to have developed from this sign.

) which would explain the theme better than the first South Arabian letter or Halleluyah Sign (A28); the especial symbol is attested in one site of Eritrea, Adi Qunsa (Vincenzo Franchini, 1964). Four series of this symbol found to be carved on rock surface in that site; where one is slight different from the others. Taking into account the significance of the more stretched hands of A28 (or the first South Arabian letter), the slightly lowered hands may signify a silent type of worshipping unlike that accompanied by dancing or shout singing. The logic behind this assumption is the literal meaning of “Selah”, which is also translated as silent in Tigrigna or in Hebrew. I would like also to note that the breast like Proto-Sinaitic character ‘S’ seems to have developed from this sign.

• It is difficult to identify its trace for the Semitic base word ’Arb‘a, probably it might have different story of derivation.

• Chumesh, five in Semitic; this is also difficult to identify the trace.

• In many Semitics the base word for the title ‘six’ is Shesh; may related to “Shush”, universally understood that it expresses the idea “be quite”. Satisfactorily explains the symbolism of the sign made from the finger lied on a mouth (![]() ).

).

• The Heb. Sheb‘a or Sheb‘a-te, meaning seven, with great degree of certitude it can be thought its root from Sebbath, the seventh day.

• Eight is read Shemoneh (& Shemon-te in Tig.). I believe the root for these varieties would be “Sem-n-yah”, the title for eighty. Simply from the attempt to establish a link to the sign of pointing gesture (![]() ); breaking the word into two, Sem meaning name and Yah the Israelite God.

); breaking the word into two, Sem meaning name and Yah the Israelite God.

• The derivation for Tesh‘a is thought from Heb. “Sha’ah”, to gaze at. It can be related to covetous looking.

• The word ’Aser, ten in Semitic, as it is described below in the next sections that it is more convincing to ascribe its origin from the twisted South Arabian letter than else.

Table 1 The names of Semitic cardinal numbers with their possible source of origin

Interpretation of the Wadi el-Hol inscriptions

Interpretation of the Wadi el-Hol inscriptions

I. Vertical Inscription

It was mentioned that the inscription comprises a total of 12 letters. There is a needless mark that creates confusion in this inscription, and some interpreters take it as a 13th letter but I ignored it in this discussion.

V1 M

The wavy line is commonly recognized as the symbol for M, from the acrophone of Semitic ‘Mem’. As mentioned above four examples of the same kind appeared in the inscriptions. It is important to note that there is slight speculation for H7 (having less waves); some scholars like Hamilton treat it differently. But I don’t see serious considerations on the sight of the author in this particular case, for there is no regular standard in the numbers of waves even for the other three instances.

The frequent occurrence of ‘M’ in these inscriptions might have a pointer implication. It helps us to suppose South Semitic dialect of the authorship, since in South Semitic languages (like Geez, Tigrigna and Amharic) “m” has a special role as initial letter in words, it can be freely added as a prefix in many noun words for extensive grammatical usage, alters noun form to “verb to be” (e.g. Ble’i is food, Mblae’ is to eat). In this way cognate grammatical process is done in these languages. Sometimes the converse (e.g Ste means (have a) drink, Meste is any type of drink), and also acts as a device for others noun words to generate from one root noun form (e.g Tshuf is script, Metshaf is book). This tradition is also common in other Semitic groups but not exceptionally common as these South Semitics.

V2 R

It is one of Mosaic symbol which was discussed thoroughly on the above; i.e. it was associated with South Arabian R.

V3 T

The cross sign (![]() ) appeared in both North and South Semitic alphabets, and used to represent for the sound ‘T’.

) appeared in both North and South Semitic alphabets, and used to represent for the sound ‘T’.

The resulting sequence from these three signs is “Mrt”, un-vocalized form of “Meriet” meaning land. The term is favorably attested as South Semitic root, which further adds strength to the support of the South Semitic authorship.

V4 Sh

This sign is also discussed above; it was suggested earlier that it can be read either Sh or S depending on the acrophone of Shabat or the Thamudic letter S (![]() ). Since a distinct character is identified in the horizontal inscription (H2) for S, we can safely attribute as Sh.

). Since a distinct character is identified in the horizontal inscription (H2) for S, we can safely attribute as Sh.

V5 W

It was explained earlier that the Phoenician Yod is a variety form of this sign. However, it is impossible to read as Y once we claim as the South Semitic dialect, where in this alphabetic system the hook sign (stylistic finger, V7) used to stand for Y instead of W unlike North Semitics. If our assumption for identifying the sign as an image of fighting man is appropriate then we shouldn’t any longer compromise with the original name of the letter as Yod (hand), otherwise the link between the generic name Yod and this specific hand gesture or action remains obscure.

There seems some interchangeable way of intonation within the Semitic language groups in the affairs of these two semivowels; probably the intermix arose from similarity of the consonants’ manner of articulation in which both are appeared to be used for the same word depending on the type of language (usually W is fashionable among South Semitic dialects, while Y is in the North Semitic dialects). See these examples of juxtapose terms of Tig. and Heb. in respective order: Werhi, Yerach (month); Werede, Yarad (went down); Wetse‘, Yatsa‘(went out). Sometimes both used in the same dialect proving that the indistinct nature of the sounds, Walad & Yalad translating in Hebrew “child”. Therefore, my estimation goes for character W, and pleasantly constructs suitable word along with the above letter and next two letters.

V6 ‘A

This is the well known letter ‘Ayin, stands for the guttural consonant ‘.

V7 Y

This is the letter for sound Y in South Semitic scripts.

If we put the results together, it is composed Sh-w-a‘-y, simply mean “seventh” in Semitic. In many Semitics languages, the suffix Y is naturally added at the end of numeric names to express the moment of occurrence.

V8 T

This an example of V3 (the character T)

V9 Z

In most previous interpretations it has been considered as boomerang (sign for G), as the claim of Brain Collosse; or alternatively viewed as figure of corner (Sign for P). But it becomes quite problematic to find any similarities with any successor of G or P in the latter Semitic alphabetic system, in which either of these letters has never experienced a doubled line sign. But seeing the sign as kneeling legs same as Canaanite syllable Ri ( ) (from “Riglu”, leg), the association with notion celestial “kneeler” (Hercules) is persuasive. But the statement has value only with the assumption that the constellation has Pre-Greek origin. Probably the idea “to kneel” implies to obey, and may have taken the figurative implication of “ ’Azan” to hear. The depiction of the Phoenician Zain with row of lines along with equatability to ’Azan may tend to suggest that its root would be from this V9 (Z), in which the Canaanite syllable Ri can be assigned as intermediary; it can also be compared to the Proto-Sinaitic sign which is made by a pair of parallel lines. If not this suggestion is true, all that can be said with certainty is that it stands for the character Z, this is based on the attempt of filling the missing link which is fortuitously surrounded by the well recognized characters.

) (from “Riglu”, leg), the association with notion celestial “kneeler” (Hercules) is persuasive. But the statement has value only with the assumption that the constellation has Pre-Greek origin. Probably the idea “to kneel” implies to obey, and may have taken the figurative implication of “ ’Azan” to hear. The depiction of the Phoenician Zain with row of lines along with equatability to ’Azan may tend to suggest that its root would be from this V9 (Z), in which the Canaanite syllable Ri can be assigned as intermediary; it can also be compared to the Proto-Sinaitic sign which is made by a pair of parallel lines. If not this suggestion is true, all that can be said with certainty is that it stands for the character Z, this is based on the attempt of filling the missing link which is fortuitously surrounded by the well recognized characters.

V10 R

This is an example of V2 (the character R).

V11 ’A

The bull’s head stands for glottal stop ( ’).

V12 L

It is usually thought as character Lamied (L). Regarding “lamied”, to which exactly refers has two different opinions: the shepherd crook and the other is the coil of rope for training of animals, from the root Lmdi “to train”. For some reason the two things might have some relation, and in this respect the term Lmdi came from the idea “rod of mouth”. Considering the term “to train” in general sense, it can be interpreted as an allegoric expression that implies chastening or judging for discipline. Correspondingly, the letter lamied ( ) seems to be the combined depiction of mouth and rod; let’s consider the Ugaritic alphabet ‘Pe’ (<), and the elongation in the lower part of letter may indicate the joining of the rod with it. In conformity of this statement, I love the expression written in Isa11:4 “…he shall smite the earth with the rod of his mouth…”.

) seems to be the combined depiction of mouth and rod; let’s consider the Ugaritic alphabet ‘Pe’ (<), and the elongation in the lower part of letter may indicate the joining of the rod with it. In conformity of this statement, I love the expression written in Isa11:4 “…he shall smite the earth with the rod of his mouth…”.

Let’s put them together; T-Z-R-A-L, it means Sown (on it). The word (T Z R A) mean “Sown”, but the last letter L is added to mark that the execution of sowing on the land.

The overall result: M-R-T SH-W-A‘-Y T-Z-R-A’-L

Translation in English: Land, (on it) sown (for) seventh

II. Horizontal Inscription

The extent of our plausibility is tested in this inscription. The recurrences of our hypothetical characters of the first script in here, plus the recognizable Proto-Sinaitic letters limit our freedom of transliteration by filling the missing links. Almost all characters are set automatically in this text, and we are in charge of whether the composed orthographies are readable or not.

After correct decipherment of all the signs, the translated words revealed that the direction of this inscription runs from left to right. Hence our H1 falls to the sign of clenched hand that appears prior to the symbol of twisted thread.

H1 Sh

The sign appears slightly different with V4 & H16, however based on some important verifications it is clear that as counterpart to these characters, and hence it is read as Sh.

H2 S

This pictographic letter stands for the phoneme S. Being the South Arabian (or Old Geez) alphabetic system serving as basic good comparative, our contrast would rest to South Arabian ( ). It does also indeed give a fine reading for the sequence in Proto-Sinaitic inscription S-376, may read S-A‘-L-Y “drawer” in Tigrigna, perhaps to mean the author. The appropriate name for this double helix containing the initial sound S might be “Sara” (Esar is its variant), the numeric ten in Hebrew. The natural reuse of some symbols motivate us to look them in other symbolic systems, hence we are able to establish the following relations: in addition to the above two alphabetic symbols used as numerals, the numeric names Elfi “ten thousand” and Miya “hundred” (the form of elocution in Hebrew & Arabic), would be traced in the alphabets Alief and Mem (pronounced as “may” or “moya” in some Semitics), and by the same technique “Sara”, being rooted from the word Esar “to fasten”, would be traced in this sign (twisted coil).

). It does also indeed give a fine reading for the sequence in Proto-Sinaitic inscription S-376, may read S-A‘-L-Y “drawer” in Tigrigna, perhaps to mean the author. The appropriate name for this double helix containing the initial sound S might be “Sara” (Esar is its variant), the numeric ten in Hebrew. The natural reuse of some symbols motivate us to look them in other symbolic systems, hence we are able to establish the following relations: in addition to the above two alphabetic symbols used as numerals, the numeric names Elfi “ten thousand” and Miya “hundred” (the form of elocution in Hebrew & Arabic), would be traced in the alphabets Alief and Mem (pronounced as “may” or “moya” in some Semitics), and by the same technique “Sara”, being rooted from the word Esar “to fasten”, would be traced in this sign (twisted coil).

From this pair a fine word Sh-S is examined. It might be compared to Semitics Shesh or Susa, meaning six or sixty from the latter. Preferably it would be much better to attribute as “six” from the context of the incorporated ideas of the contents of the inscriptions, the descriptions are offered in the next discussions.

H3 M

This is an example of V1 (the character M).

H4 D

This is one of the tricky signs which cannot be quickly identified. In the early alphabetic systems sometimes the character D is appeared to depict a triangle, for some grounds it may be associated to the tail part of fish. In this support, the account of constellational approach can excellently help to explain the argument. In his “History of the Zodiac”- AfO 16 (1952-53), p.p 219, B.L van der Waerden states that the constellation tails (zibbati mesh in Akkadian) have changed its name and known by riski nuni (the band of fishes) in the later tablet (c.400 BC). Hamilton’s suggested that fish’s typological earliest graphic form is ascertained to fins.

This letter sign (H4) is a form of an early Phoenician D ( ); the difference is only in that the former has bisector in its middle. There might be two explanations for this: it would be an attempt of portraying two tails, agreeing with the plurality of the name “tails”, or intended to depict the natural split of the tail of fishes. It should be noted that the early Proto-Sinaitic whole figure of fish wouldn’t be related to the celestial fish. It might have different derivation, because the celestial fishes chronologically came in much later dates. Thus, it is not surprising that in the Sinai inscription 352 (Fig. 8), issued by W.M.F. Petrie, we find the fish and tail together.

); the difference is only in that the former has bisector in its middle. There might be two explanations for this: it would be an attempt of portraying two tails, agreeing with the plurality of the name “tails”, or intended to depict the natural split of the tail of fishes. It should be noted that the early Proto-Sinaitic whole figure of fish wouldn’t be related to the celestial fish. It might have different derivation, because the celestial fishes chronologically came in much later dates. Thus, it is not surprising that in the Sinai inscription 352 (Fig. 8), issued by W.M.F. Petrie, we find the fish and tail together.

Fig. 8 Sinai inscription 352

H5 ’A

This is an example of V11 (the glottal stop ’)

H6 W

This is an example of V5 (the character W)

The four letters give the Semitic word M-D-A-W, same like Hebrew “Middah” or Aramaic “Mindaw”, tribute in money. We don’t trace any term in the same exact sense in Tigrigna or in its relative linguistics, however the word Midhan “saving”, in its original context probably would mean like “ransom”, the price required to save somebody. So far the two words are consistently related to each other “A tribute of six”.

H7 M

This is an example of V1 (the character M)

H8 Z

This is an example of V9 (the character Z)

H9 N

The sign represents the snake, the pictographic letter which stands for sound N in the Proto-Sinaitic alphabets (from Semitic nahas). There are two more examples in this inscription.

The next three letters in the sequence come up with the harmonious word M-Z-N “to weigh”.

H10 H

We have discussed in the first topic that the figure of worshiping (or hallelujah) is used to write for sound H.

H11 N

This is an example of H9 (the character N)

H12 M

This is the fourth example of V1 (the character M)

The combination H-N-M excellently forms the vocalized Hebrew chinam “gift”(where the first letter in this case is pronounced with the strong H). As far as explicit form is needed the term couldn’t be found in Tigrigna. The logical flow of the ideas is yet uninterrupted even at this part.

H13 N

This is third example of H9 (the character N)

H14 L

This is an example of V12 (the character L)

H15 B

This is the instance of Proto Sinaitic alphabet Bayt (house), carrying the sound value B.

H16 Sh

This is an example of V4 (the character Sh)

The last four automatically set characters simply read N-L-B-SH, translated as “for garment”, where N acts as the preposition “for” in Tigrigna grammar, and LBSH rendered similarly in most Semitic languages. All the words kept consistency, neither of the resulting words is odd.

The overall reading gives us this sentence: SH-S M-D-A-W M-Z-N H-N-M N-L-B-SH

Translation in English: A tribute of six weighed (as) a gift for garment

Comments are currently closed.